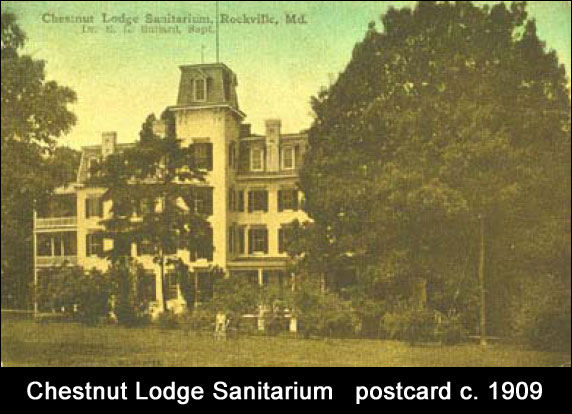

Chestnut Lodge Sanitarium

The weird tentacles and unspoken “degrees of separation” of those involved with Chestnut Lodge over its century of mental health treatment are pervasive and only beginning to be unearthed. Feedback, stories, information.

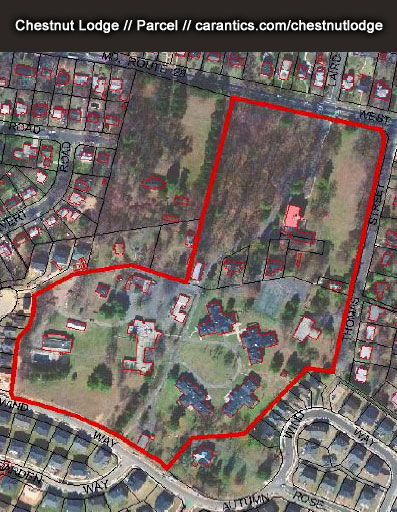

An old medical treatment / insane asylum smack in the heart of Rockville (Montgomery county, 20 miles northwest of Washington, DC; home to highest concentration of Ph.D.’s in the country). It was internationally known (google for “chestnut lodge”), hard wired into the psych community after nearly a century of treating many long-term, profoundly disturbed psych patients and mute, catatonic and “hopeless schizophrenics.” Briefly a resort hotel, it became the quintessential psychiatric sanitarium. A young neighbor noted it feels like Hannibal Lechter could have been there.

Closed in 2001, its 20+ acres and 20+ buildings (several of which are historic) still seem eerily fresh, frozen, timeless. We’ve gathered lots of information (resurrecting the original website), including maps, photos, and stories. Cracked CIA agents were possibly treated, and edgy pharmacological studies were reportedly conducted there. Famous families often committed nutty relatives against their will. Several books have been written about Chestnut Lodge, a peerlessly intense facility that still chills and rivets attention with, well, an insanely creepy history and presence.

Not a great place to lose your bearing, your mind or your life, it’s definitely worthy of a wild scare or two. Screams and odd goings-on have been reported by nearby neighbors since its closure and before, but those are probably just pranks… Coincidentally, there is a large funeral home three blocks away.

CIA & Prominent Patients

Chestnut Lodge is intertwined with CIA conspiracies in multiple ways, including odd deaths of interesting persons including the owner of the Washington Post and Frank Olson, Army liaison to CIA LSD chemical warfare.

Chestnut Lodge, a psychiatric hospital in Rockville, Maryland, had a reputation for treating high-profile individuals, including some notable figures tied to significant events and organizations. Here are some known or rumored patients of Chestnut Lodge:

1. Philip Graham

- Background: Publisher of The Washington Post and husband of Katharine Graham.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Philip Graham was treated at Chestnut Lodge for severe mental illness, particularly depression and manic episodes, before his tragic suicide in 1963.

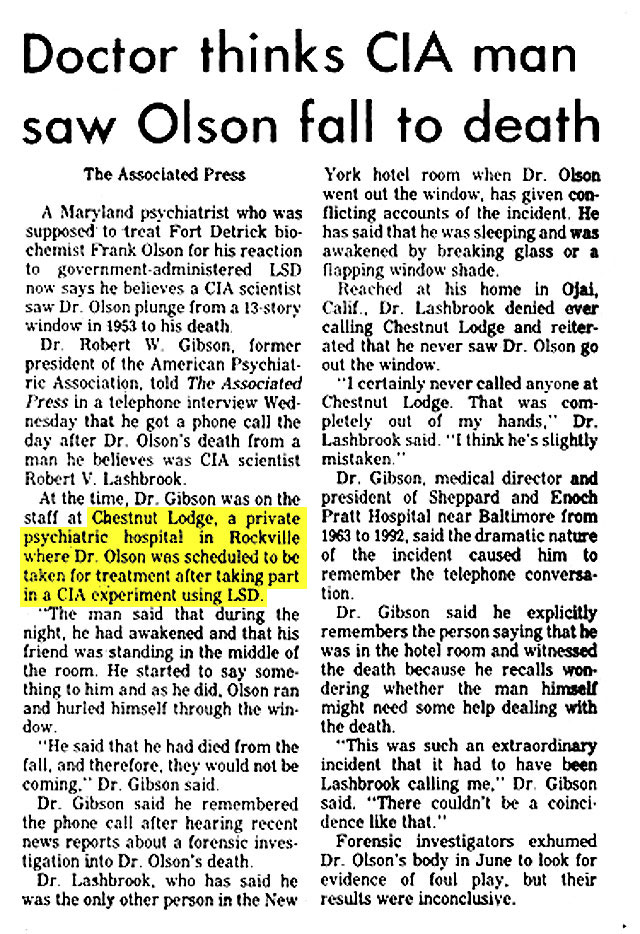

2. Frank Olson

- Background: A U.S. Army biochemist and CIA employee associated with biological weapons research.

- The HBO mini-series WORMWOOD (which ended up being a kind of white-wash decepticon) very loosely concerns the true evil machinations involving Olson, who more directly ‘wanted out (of CIA)’ after learning that CIA was directly involved in the cavalier 1951 mass-dosing of a French town (Pont St Esprit incident) with LSD / Ergot for scientific study: ‘What would happen if an entire town was doped up…’ (Pont-Saint-Esprit is famous as the town of origin of Michel Bouvier, a cabinetmaker, who was the ancestor of John Vernou Bouvier III, father of Jacqueline Kennedy.) See immediately below:

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Olson is believed to have sought treatment at Chestnut Lodge following a mental health crisis, reportedly exacerbated after he was unwittingly dosed with LSD as part of the CIA’s MKUltra program. His mysterious death in 1953 remains the subject of numerous conspiracy theories.

In his 2009 book, A Terrible Mistake, author and investigative journalist Hank P. Albarelli Jr writes that the Special Operations Division of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) tested the use of LSD on the population of Pont-Saint-Esprit as part of its MKNAOMI biological warfare program, in a field test called “Project SPAN”.[15] According to Albarelli, this is based on CIA documents held in the US National Archives and a document supplied to the 1975 Rockefeller Commission that investigated CIA activities. Albarelli’s view was reported widely after the book’s publication, including by The Daily Telegraph, France 24 and BBC News.[20] The attribution of the poisoning to the CIA in Albarelli’s book has been criticized.[19] Historian Steven Kaplan, author of an earlier book about the events, said that this would be “clinically incoherent: LSD takes effects in just a few hours, whereas the inhabitants showed symptoms only after 36 hours or more. Furthermore, LSD does not cause the digestive ailments or the vegetative effects described by the townspeople.”[21]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1951_Pont-Saint-Esprit_mass_poisoning

“One of the oldest psych research hospitals on Earth, geographically neighboring and in the shadow of major CIA MK research and military biowar and MK operations, but somehow there are zero connections. LOL. Now THAT is a conspiracy! Montgomery County, Maryland, epicenter of these hob-nobbings, has the highest concentration of Ph.D.s in the country and maybe the world. There is absolutely deep cross-contamination of efforts, programs, ideologies, pursuits, intrigues.”

3. Sybil Isabel Dorsett (Shirley Ardell Mason)

- Background: Known as “Sybil,” she was the subject of the famous book and later films that documented her diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder (DID).

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Sybil was a patient of Dr. Cornelia Wilbur, who worked closely with the hospital.

4. Robert Lowell

- Background: Pulitzer Prize-winning poet.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Lowell received treatment there for bipolar disorder, which he detailed in some of his poems and letters.

5. James Forrestal

- Background: The first U.S. Secretary of Defense.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Forrestal reportedly underwent treatment for severe mental illness, including paranoia and depression, prior to his death by suspected suicide in 1949.

6. Anne Sexton

- Background: Pulitzer Prize-winning poet.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Sexton underwent treatment there for severe depression and wrote extensively about her struggles with mental health.

7. Ruth Ford

- Background: An actress and member of New York’s literary and art scenes.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Ford reportedly received treatment at the facility during her lifetime.

8. Judy Garland (!)

- Background: Celebrated actress and singer, best known for her role in The Wizard of Oz.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Garland reportedly sought treatment at Chestnut Lodge during her struggles with substance abuse and mental health issues.

9. Rafael Osheroff

- Background: A nephrologist who became central to a landmark legal case concerning psychiatric treatment.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Osheroff was a patient in the 1980s and later sued the institution, alleging negligence for not providing pharmacological treatment. This case sparked significant debate about treatment approaches in psychiatry. See

10. Michelle Shocked

- Background: Musician.

- Connection to Chestnut Lodge: Admittedly received treatment at the facility.

“Being in a mental institution has all of the contours and shapes of any other kind of institutional life- and as I said earlier, the first 22 years of my life were basically spent in institutions of one kind or another. In the mental institution, activities are scheduled and very rigid. You don’t stop when you finish the project. You stop when the schedule says to stop. The people who work there, some of them are good people, but the institution pretty much forbids them from functioning outside a certain standard of compassion. The institutional mentality told the staff, “You can have one percent of compassion and ninety-nine percent follow-the-rules.

And this mindset is a barrier that makes it almost impossible for staff to show the depth of true human compassion that institutionalized people desperately need. When you are in an altered state, hospitalized, drugged, isolated from the people you care about, the most important gift you could receive would be a genuine, caring connection with another human being. The lack of compassion, in my mind, is the single biggest failing of the mental health system.

…the therapist, a woman named Isabel Pierce, pointed out something that I found very significant. She said, “You’re not crazy. You’re just poor. And I found this explanation very revealing. When my mother had me committed, one of her reasons was that she thought that I was anorexic. And I wasn’t anorexic, I just didn’t have any money for food…I’ve come to realize that nutrition really contributes enormously to your mental state.”

–Michelle Shocked (the singer)

THIS is excellent, definitely worth a read.

PDF below:

The hospital also became infamous for pioneering but controversial psychoanalytic approaches to mental health treatment. These methods often attracted individuals from influential or intellectual backgrounds who sought its experimental therapies.

Don Parcher (2019): I’m helping a former resident/patient (Bob Bernstein) with a book (The Sheik and the Shadow) which includes extensive details about his experiences at Chestnut Lodge.

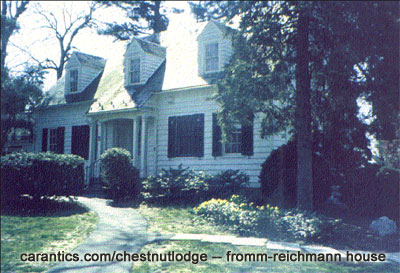

I read Freida Fromm Reichman’s main text ‘Principles of Intensive Psychotherapy’ many years ago and still go back to dip into it, a great book. I’m glad her cottage-house is still here, and as someone who does believe in ghosts I suspect she still comes back for a visit.

Dr Michael Woodbury and Cold Wet Sheet Pack (CWSP)

Most of the schools and medical facilities such as Chestnut Lodge closed after the FLEXNER REPORT was released in 1910. ~4:00 in

Woodlawn hotel went bankrupt before it even opened. ~7:00 in

Dextar Bullard felt that dream analysis was crucial.

Chestnut Lodge Insane Asylum

“Think about this: No one left alive knows all its secrets…this place defines insane.”

Chestnut Lodge Insane Asylum, 500 West Montgomery Ave., in the heart of Rockville, Maryland. A sanitarium for the “profoundly regressed” psychotic, “hopelessly schizophrenic,” borderline personality disorder (BPD), and other seriously afflicted psychiatric and “mental” patients.

“…I live nearby…we used to hear screams…my son calls it Hannibal’s House…we just want it gone…”

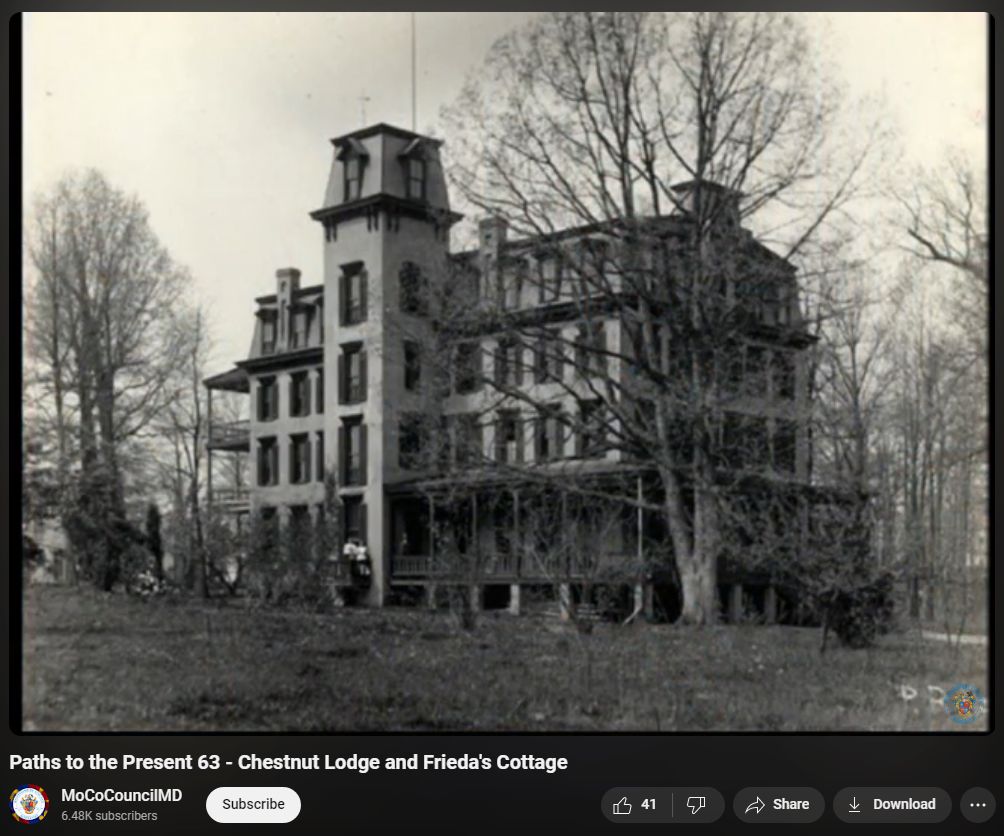

An historical DC suburban resort hotel turned mental hospital. Built in 1886. Closed in 2001. Historical. Off-limits. Eery. Taboo. Haunted? Unforgettable. Irresistable.

“…you shouldn’t imagine what was going on in there… it’s better if you don’t know, if no one knows…” –local resident, retired researcher

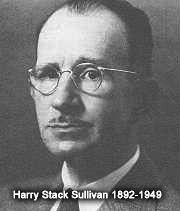

Owned and run for almost a century by three generations of psychiatrists in the Bullard family. Internationally renowned. Over tweny buildings and 125 chestnut trees on over twenty acres, including patient lodgings and various buildings of historic/famous architecture. Notable staff included Frieda Fromme-Reichmann, psychoanalyst (c.1957), Harry Stack Sullivan, Alfred H. Stanton (The Mental Hospital), Ann Alaoglu, David Rioch, Harold Searles & Robert Morris (Menninger Clinic), Robert Cohen (NIH), Ann-Loiuse S. Silver, Wayne S. Fenton, M.D. (CNL Director of Research), Jan Foudraine (Swami Deva Amrito) (Not Made of Wood), Johnathan D. Tuerk, and Clara Thompson.

“…one wonders if it would be possible–indeed, if it would even be permitted–for people like Sullivan and Fromm-Reichmann to work with patients the way they did 50 years ago…” –psychiatry today

Between I-270 and Rockville, Maryland. North from DC along I-270 “BioTech Alley.”

Exit 7 onto Route 28, into Rockville: Right at second light, opposite of Laird St., into the trees.

“…cheery pictures, great scientific contributions, but this is not a happy place…”

san·a·to·ri·um // n. pl. san·a·to·ri·ums or san·a·to·ri·a

1. An institution for the treatment of chronic diseases or for medically supervised recuperation.

2. A resort for improvement or maintenance of health, especially for convalescents. Also called sanitarium.

Regarding the postcard image: the postcard shows the picturesque east facade of the hospital, the side facing the “parade grounds” clearing, the side with only a pedestrian approach. Modern pictures are usually taken from the paved driveway, which approaches from the north and shows the hospital’s slender north facade. Therefore, the “tower” structure on earlier images appears to the left of the modern pictures which unfortunately do not convey the intended grandeur of Chestnut Lodge.

Quotes”It’s extraordinarily creepy, especially at night. The deceptive quaintness, hundreds of tall trees without any underbrush, the seriously pot-holed driveway, the dreariness. Honestly, it looks straight out of Silence of the Lambs. You can almost hear the muffled screams of restrained psychotics, the dull thuds of autistic headbutting, the weird gurgling, humming and shrieks of the profoundly disturbed and disabled, and an almost palpable swirling madness. If St. Elizabeth’s nuthouse gave you chills, then Chestnut Lodge is what comes next.”

“…Be mindful that Sullivan and Fromm-Reichmann worked with profoundly regressed patients, some diagnosed as ‘hopelessly schizophrenic’ and others who were not so easy to categorize, using psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. Medicating drug therapy was just being established, and most psychiatrists used electroshock therapy, sleep therapy, and other bizarre treatments…”

Regarding electroshock therapy, watch “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest” to see Jack Nicholson’s researched, realistic depiction of one form of the treatment: “Jack researched the role by showing up at Oregon State Mental Hospital in Salem two weeks before he was required, where he persuaded hospital authorities to let him mingle with the most disturbed patients, eating in their mess halls and closely observing their speech patterns and body movements. He even watched patients undergoing the same shock treatments McMurphy would be subjected to in the film, in order to make his depiction more authentic. ‘Usually, I don’t have much trouble slipping out of a film role,’ he admitted, ‘but here, I don’t go home from a movie studio. I go home from a mental institution. And it becomes harder to create a separation between reality and make-believe.’ –http://www.littlereview.com/goddesslouise/articles/nichcuck.htm

“…My mother worked there many years ago. Parts were strictly off-limits, presumably for the profoundly or criminally insane, or hushed for the military. [The CIA apparently used the facility. Press, accounts, and documentation from military mind control programs, including ‘MK/ULTRA’ (mind control), ‘ARTICHOKE’ (extreme interrogation), ‘PAPERCLIP’ (the imported Nazi-scientist/war criminals roles in both), ‘MK/SHADE’, ‘OFTEN’, ‘MK/MARKER’, ‘MK/DELTA’, ‘BLUEBIRD’, ‘MK/NAOMI’, ‘PHOENIX’, and ‘MK/SEARCH’ sometimes directly reference Chestnut Lodge. [read].] There are rooms for administering almost every treatment then imaginable. The scariest part is not that you could go inside, but that they could keep you inside and do anything to you. [see michelle shocked] Some people who went there never left the same. Sometimes that was good, but other times…”

Do not believe the Whitewash. It was not as widely claimed. Abide the whispers, the occulted military, the intrigues.

“… I was given large doses of some kind of drug to calm me down…I was sent to Chestnut Lodge…the psychiatric experimental prison…” —The Journal of Judith Beck Stein

“Interviews with Sydney Gottlieb [CIA Special Projects: MKULTRA mind-control, LSD psychedelic research, societal and cultural manipulation] in 1999 and declassified documents [via FOIA] reveal that one of the substances considered for use against Castro was ‘a new convulsive compound which produced a condition similar to electroshock.’ Called ‘Indoklon’ by its developers at the Bressler Research Laboratory of the University of Maryland, its odorless vapors ‘produce immediate convulsions accompanied by arching of the back, stiffening of the neck and unconsciousness.’ Human testing with the compound had been conducted at Spring Grove State Hospital, Baltimore, and at Chestnut Lodge in Rockville, Md. Gottlieb also proposed that a special aerosol spraying device, designed by scientists at Fort Detrick’s [Frederick, Maryland] Special Operations Division, be employed to contaminate the radio studio where Castro broadcast his frequent speeches. The device was to be filled with the powerful hallucinogenic BZ, which scientists have described as being ‘about ten times more powerful than LSD.'” —wnd.com

“Another Gottlieb subproject under MK-ULTRA conducted experiments with LAE, a lysergic-acid derivative, for the purpose of inducing depersonalization and a schizophrenia-like condition in test subjects. Gottlieb referred to the result in these cases as ‘reversible chemical lobotomy’—suggesting that the effects wear off. There were 429 tests of this type reported on normal and psychotic individuals in the first year of MK-ULTRA. (As in other such tests mentioned in the CIA documents, there was no indication of where the test subjects came from and whether they were ‘witting’ or ‘unwitting.’) Still another MKULTRA subproject called for a psychological analysis of the effects of LSD on 220 college students who were tested in 1953.” —FOP

“Hock’s landmark thesis that LSD was a psychotomimetic or madness-mimicking agent caused a sensation in scientific circles and led to several important and stimulating theories regarding the biochemical basis of schizophrenia. This in turn sparked an upsurge of interest in brain chemistry and opened new vistas in the field of experimental psychiatry. In light of the extremely high potency of LSD, it seemed completely plausible that infinitesimal traces of a psychoactive substance produced through metabolic dysfunction by the human organism might cause psychotic disturbances. Conversely, attempts to alleviate a lysergic psychosis might point the way toward cutting schizophrenia and other forms of mental illness. FOOTNOTE: While the miracle cure never panned out, it is worth nothing that Thorazine was found to mollify an LSD reaction and subsequently became a standard drug for controlling patients in mental asylums and prisons.” –http://www.a1b2c3.com/drugs/lsd09a.htm

“…The CIA made preparation to treat Olson at Chestnut Lodge, but before they could, Olson checked into a New York hotel and ‘threw himself out’ from his tenth story room…” –Dave McGowan, https://davesweb.cnchost.com

“…it was agreed that Olson should be placed under regular psychiatric care at Chestnut Lodge, an institution closer to his home and what had CIA-cleared psychiatrists on its Rockville, Maryland, staff. Arrangements were made for Frank Olson’s immediate admission to the hospital. In what was undoubtedly a remarkable coincidence, the doctor who served as the admitting physician was Dr. Robert W. Gibson — the 25-year old son of Walter Gibson. Walter Gibson was one of magic’s most prolific writers and editors, though the general public would know him best as the author of ‘The Shadow.’ [famous radio entertainment program] He was also a close friend and colleague to John Mulholland…Harold Abramson…” —Conjurors Magazine ‘The Sphynx & The Spy’

(See “Mind Control Murder” by Principal Films for A&E’s Investigative Reports series. See also John Marks’ 264-page, 1977 book, “The Search for the Manchurian Candidate”)

“…explore connections with the NIMH (nat’l institutes of medical/mental health), the NMRI (Navy medical research institute), and the Navy’s CHATTER program from 47 to 53…”

“When the CIA, formed in 1947, began really operating in the 50’s, it was given 6% of the defense department’s budget, with black-out status. That’s an awful lot, in secret…”

From the book “Acid Dreams”: The CIA studied a veritable pharmacopoeia of drugs with the hope of achieving a breakthrough. At one point during the early 1950s Uncle Sam’s secret agents viewed cocaine as a potential truth serum. “Cocaine’s general effects have been somewhat neglected”, noted an astute researcher. Whereupon tests were conducted that enabled the CIA to determine that the precious powder “will produce elation, talkativeness, etc.” when administer by injection. “Larger doses,” according to a previously classified document, “may cause fearfulness and alarming hallucinations.” The document goes on to report that cocaine “counteracts… the catatonia of catatonic schizophrenics” and concludes with the recommendation that the drug be studied further…A number of cocaine derivatives were also investigated from an interrogation standpoint. Procaine, a synthetic analogue, was tested on mental patients and the results were intriguing. When injected into the frontal lobe of the brain through trephine holes in the skull, the drug “produced free and spontaneous speech within two days in mute schizophrenics”. This procedure was rejected as “too surgical for our use”. Nevertheless, according to a CIA pharmacologist, “it is possible that such a drug could be gotten into the general circulation of subject without surgery, hypodermic or feeding.” He suggested a method known as iontophoresis, which involves using an electric current to transfer the ions of a chosen medicament into the tissues of the body.” // Injections; test drugs; secret government programs; unlimited funding; heady, unaccountability; electric shocks and edge treatments; bioweapons research (Ft. Detrick, Ft. Meade) and testing (Aberdeen, Edgewood Arsenal); mute & catatonic schizophrenics; and the highest number of Ph.D.’s in the country (DC suburbs); it’d be impossible to find a nearby medical or mental facility not wholly intertwined and involved.

(See “Acid Dreams” by Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain, Grove Press, 1985 ISBN 0-394-55013-7. Paraphrased by totse.com: The CIA realized that an adversary intelligence service could employ LSD “to produce anxiety or terror in medically unsophisticated subjects unable to distinguish drug-induced psychosis from actual insanity”. The only way to be sure that an operative would not freak out under such circumstances would be to give him a taste of LSD (a mind control vaccine?) before he was sent on a sensitive overseas mission. Such a person would know that the effects of the drug were transitory and would therefore be in a better position to handle the experience. CIA documents actually refer to agents who were familiar with LSD as “enlightened operatives”.)

“…with deep conviction that no patient is beyond hope, they focused on deep psychoses there instead of less-severe neuroses…those people were the real deal…those they took in were the lost souls no one else would or could…”

“…what Chestnut Lodge has been about over the years. We have worked with the severely ill generally, those who need longer-term treatment, and often when it wasn’t working out for them elsewhere, they would be referred here…” –Dr. Robert Kurtz, medical director, Chestnut Lodge

“…with all its crazies over the decades, that place is intertwined with and mired in so much incredibly nutty stuff…”

“…an in-depth study of inpatients at a hospital in Maryland during the years 1950 through 1975 and their 30 years of clinical and supervisory experience at Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, Hoffman and McGlashan present four case studies to chart the etiology, long-term course, and clinical manifestations of BPD…” [see ‘Developmental Model of Borderline Personality Disorder’ by Patricia Hoffman of Judd University of California-San Diego, and Thomas H. McGlashan of Yale School of Medicine.]

“…a fearful place of drugged screams and troubled mumblings…”

CIA MKULTRA Experimentation

(1) Sarah Foster, Meet Sidney Gottlieb – CIA Dirty Trickster (1998):

It seemed Stanley Glickman had everything going for him. An American, Glickman was young, living in Paris, and busy carving out a successful career for himself as an artist. Then one evening in late October 1952, his world crashed to an end. He accepted an invitation from an acquaintance to join him and some fellow Americans at the Cafe Select, a popular spot among writers and artists. There, the conversation turned into a heated political debate lasting several hours. When Glickman decided it was time to leave, one of the men offered to buy him a drink to soothe any hard feelings. Rather than ask the waiter, the man himself went to the bar and brought drinks back to the table. Glickman noticed he had a club foot.

Thirty years later he learned this was a physical characteristic of Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, who headed the chemical division of the technical services staff with the Central Intelligence Agency. In an affidavit filed in court, Glickman recalled that halfway through his drink he “began to experience a lengthening of distance and a distortion of perception” and saw that “the faces of the gentlemen flushed with excitement as they watched the execution of the drink.”

One of the men told him he’d be capable of “working miracles.” No miracles occurred, but as Glickman left the cafe he “experienced distortions of color and other hallucinations.” He believed he had been poisoned. Next morning, he was “hallucinating intensely.” For the next two weeks he “wandered in the pain of madness, delusion and terror.”

On Nov. 11, he returned to the Cafe Select, where he sat and simply waited – with his eyes closed – until someone noticed him, and he was driven by car to the American Hospital of Paris. He was there over a week, during which time he was given electroshock and, he believed, additional hallucinatory drugs. Finally a friend came, helped him sign out, and took him to his studio where he remained, a virtual recluse, for the next 10 months – living in a psychedelic nightmare of terror and hallucinations.

When friends of his brother-in-law’s family saw him on the street and realized the condition he was in, they contacted his family, who made arrangements for him to be brought back to the United States in July 1953. Glickman never painted again.

He held odd jobs and regained his physical strength, but his mental powers were never the same; his artistic talents were destroyed. Nor was he able to lead a normal social life. If Glickman’s story is true, he would have been one of the earliest victims of the MK-ULTRA project, one program of which involved slipping d-lysergic acid diethylamide – better known as LSD – to persons without their knowledge or consent, then watching their reactions. The CIA’s secret project was not formally initiated until April 1953, but there are accounts of earlier experimentation.

When the public learned of these experiments over 20 years later, Glickman realized he had been one of the victims.

In 1977, Glickman’s sister, Gloria Kronisch, sent her brother an article she had read about how the CIA had experimented with LSD on unsuspecting people in foreign countries during the 1950s. At this time, the Senate Committee on Human Resources, chaired by Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-MA, began holding hearings on CIA experimentations on humans, and the CIA was asked to identify its victims.

The CIA identified 16 unwitting subjects of LSD tests in the United States, but denied conducting such experiments overseas. Watching the hearings, Glickman knew that’s what happened to him, no matter what the CIA claimed. A friend traveled to Washington to gather information about the agency’s drug experiments. Most of the records had been destroyed, at Gottlieb’s orders, in 1973.

[Despite their lies under oath about only 30 universities and research institutions being majorly involved, some CIA financial records and receipts, thought destroyed but turned up by John Marks (author of the resulting “The Manchurian Candidate”), proved at least 86 universities and research institutions were majorly involved in the project. That’s three times worse than what they admitted under oath. Wonder how many were actually involved? –sourced from “Project MKULTRA: The CIA’s Program of Research in Behavioral Modification” printed by the GAO and available at lulu.com and other places online.]

(2) US Official Poisoner Dies, CounterPunch (April, 1999)

For many years, most notably in the 1950s and 1960s, Gottlieb presided over the CIA’s technical services division and supervised preparation of lethal poisons, experiments in mind control and administration of LSD and other psychoactive drugs to unwitting subjects. Gottlieb’s passing came at a convenient time for the CIA, just as several new trials involving victims of its experiments were being brought. Those who had talked to Gottlieb in the past few years say that the chemist believed that the Agency was trying to make him the fall guy for the entire program. Some speculate that Gottlieb may have been ready to spill the goods on a wide range of CIA programs.

Incredibly, neither the Times nor the Post obituaries mention Gottlieb’s crucial role in the death of Dr. Frank Olson, who worked for the US Army’s biological weapons center at Fort Detrick. At a CIA sponsored retreat in rural Maryland on November 18, 1953, Gottlieb gave the unwitting Olson a glass of Cointreau liberally spiked with LSD. Olson developed psychotic symptoms soon thereafter and within a few days had plunged to his death from an upper floor room at the New York Statler-Hilton. Olson was sharing the room with Gottlieb’s number two, a CIA man called Robert Lashbrook, who had taken the deranged man to see a CIA-sponsored medic called Harold Abramson who ran an allergy clinic at Mount Sinai, funded by Gottlieb to research LSD.

By the early 1960s Gottlieb’s techniques and potions were being fully deployed in the field. Well-known is Gottlieb’s journey to the Congo, where his little black bag held an Agency-developed biotoxin scheduled for Patrice Lumumba’s toothbrush. He also tried to manage Iraq’s general Kassim with a handkerchief doctored with botulinum and there were the endless poisons directed at Fidel Castro, from the LSD the Agency wanted to spray in his radio booth to the poisonous fountain pen intended for Castro that was handed by a CIA man to Rolando Cubela on November 22, 1963.

Even less well remembered is one mission in the CIA’s Phoenix Program in Vietnam in July of 1968. A team of CIA psychologists set up shop at Bien Hoa Prison outside Saigon, where NLF suspects were being held after Phoenix Program round-ups. The psychologists performed a variety of experiments on the prisoners. In one, three prisoners were anaesthetized; their skulls were opened and electrodes implanted by CIA doctors into different parts of their brains. The prisoners were revived, placed in a room with knives and the electrodes in the brains activated by the psychiatrists, who were covertly observing them. The hope was that they could be prompted in this manner to attack each other. The experiments failed. The electrodes were removed, the patients were shot and their bodies burned.

(3) Elaine Woo, Los Angeles Times (4th April, 1999)

James Bond had Q, the scientific wizard who supplied 007 with dazzling gadgets to deploy against enemy agents. The Central Intelligence Agency had Sidney Gottlieb, a Bronx-born biochemist with a PhD from Caltech whose job as head of the agency’s technical services division was to concoct the tools of espionage: disappearing inks, poison darts, toxic handkerchiefs.

Gottlieb once mailed a lethal handkerchief to an Iraqi colonel and personally ferried deadly bacteria to the Congo to kill Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. It wasn’t his potions that eventually did in the two targets, but Gottlieb, once described by a colleague as the ultimate “good soldier,” soldiered on.

Poisons and darts were not his sole preoccupation during 22 years with the CIA. He labored for years on a project to unlock and control the mysterious powers of lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD. Could it be a potent spy weapon to weaken the minds of unwilling targets?

In the early 1960s, Gottlieb was promoted to the highest deputy post in the technical services operation. By 1967, he had risen to the top of the division, guided by his longtime CIA mentor, Director Richard Helms. At that time, LSD was not a secret anymore. While the CIA was still examining the drug’s possibilities as a means of mind control, many young Americans were dropping the hallucinogen as a vehicle of mind expansion and recreation. America was tuning in, turning on and dropping out, thanks, in part, to the CIA’s activism in the ’50s in the name of national security.

It was not until 1972 that Gottlieb called a halt to the experiments with psychedelics, concluding in a memo that they were “too unpredictable in their effects on individual human beings… to be operationally useful.”

He retired the same year, spending the next few decades in eclectic pursuits that defied the stereotype of the spy. He went to India with his wife to volunteer at a hospital for lepers. A stutterer since childhood, he got a master’s degree in speech therapy. He raised goats on a Virginia farm. And he practiced folk dancing, a lifelong passion despite the handicap of a clubfoot.

Update 2023-08

Due to its highly peculiar symptoms after ingestion, the naturally-occuring toxic rye mold Ergot was long thought responsible for the 1951 mass-poisoning in the French town Pont Saint-Esprit; however, in 2009 an American investigative journalist, Hank Albarelli, revealed a CIA document labelled: “Re: Pont-Saint-Esprit and F.Olson Files. SO Span/France Operation file, inclusive Olson. Intel files. Hand carry to Belin – tell him to see to it that these are buried.”

A costly distraction, the NETFLIX mini-series WORMWOOD ridiculously omits any serious investigation into or even mention of LSD, CIA, military MK as relating to Pont Saint-Esprit. NETFLIX Founder Marc Bernays Randolph is the great grand-nephew of Edward Bernays, creator of modern propaganda and himself the nephew of Sigmund Freud.

Sources

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=cinemax+special+about+frank+olson

http://www.dhushara.com/psyconcs/esprit.pdf

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-10996838

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=cia%2C+olson%2C+ives+st+esprit

You can still hear them screaming

People think we must have come such a long way, but they forget that “…America’s mental health system is still the shame of the nation…” — narpa.org

“…inpatient psychotics included those with schizophrenia, autism, and multiple-personality disorders, among other severe psychopathologies and various pschoses…”

“…people often confuse creativity with insanity. There is no creativity in madness…” –Joanne Greenberg (pseudonym Hannah Green), I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden is a fictionalized depiction of Joanne Greenberg’s (pseudonym Hannah Green) treatment experience at Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, Maryland, during which she was in psychoanalytic treatment with Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. The book takes place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, at a time when Harry Stack Sullivan, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, and Clara Thompson were establishing the basis for the interpersonal school of psychiatry and psychoanalysis, focusing specifically, though by no means exclusively, on the treatment of schizophrenia.

“What you have to understand is that I hear them all the time. Anybody could. You have to be perceptive, but you can definitely hear them,” he says, his eyes suddenly turning serious. His grave demeanor is understandable, for the ‘them’ to which he is referring are the sounds that he had heard while making nightly rounds of the hospital. “You hear them on the grounds,” he continues. “It is crying – sometimes screaming. We had patients who would scream constantly and who suffered. Sometimes at night you can still hear them scream and moan.”

“…Chestnut Lodge was founded in the early twentieth century as a family business by Ernest Bullard, M.D. Three generations of Bullards served as its medical director. It was a pioneer in the intensive psychodynamic-psychotherapeutic treatment of serious mental illness, and two legendary psychiatrists-psychoanalysts-Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, M.D., and Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D.-served on the Chestnut Lodge staff…” –Recent Past Network

“…Chestnut Lodge was a pioneer in the intensive treatment of serious mental illness…” –Psych.org

“…this place has been the often purposeful but sometimes unwitting home to perhaps thousands of studies, reports, tests, observations, cohorts, and data…” [1] [2] [3]

“…after nearly a century, this place and these people were hooked up, wired into the psych community: National Institutes of Health and Ford Foundation grants, interships, training, lectures, numerous publications and studies, in-patient lodging, live-in doctors, a research facility on the grounds…”

“…The institutional nature of Chestnut Lodge, involving care and exclusion, was an obstacle…” –pubmed, nat’l lib. medicine, nat’l inst. heath

“…Chestnut Lodge is a small, private psychiatric hospital in Rockville, Md, specializing in the long-term residential treatment of severely ill (and usually chronic) psychotic and borderline patients. Four hundred forty-six (72%) of the patients treated at Chestnut Lodge between 1950 and 1975 were followed up an average of 15 years later…” –pubmed, nat’l lib. medicine, nat’l inst. heath

Location Details & Specifics

A driveway snakes around to the other buildings in the rear of the main hospital. Numerous inhabited houses are within a stone’s throw, easily within earshot. This is downtown Rockville, surprisingly near the courthouse and I-270.

Power meters are missing from most buildings. Several post-midnight visits met with no resistance or inquiry. No guards, dogs, lights, or alarms. All windows and doors appear intact and locked except at least one. Wire-glass windows and flimsy doors exist on the main lodge and support structures; thick metal doors seal the modern inpatient lodgings. The barn appears relatively open, and the community/activity building is being gutted or ransacked [Jan 2005] (possibly for demolition or reuse).

What is most surprising is that the Chestnut Lodge is actually a rather huge, self-sufficient treatment campus that was designed for taking and keeping patients for years or longer, to span all phases of treatment including, ultimately, pharmacology (drug therapy). Equally surprising is that it exists basically smack in the middle of Rockville! Few people know what it is, fewer know where, and no one left alive knows all its secrets.

Main Chestnut Lodge: 40+ rooms, 4 stories above ground, at least 2 below, all brick. Additional on-grounds buildings and facilities include(d): laundry, nurses’/servants’ quarters, maintenance barn, tool shed, facilities buildings, stable (refitted), windmill (demolished), ice house, carriage house, kitchen, laundry, four patient lodgings (resemble elderly assisted living condos), recreational gymnasium building, outdoor pool, common parade grounds, gazebo, mature tree clearings, tennis courts and paved areas, and shared community activity center (this is the one with historic/famous architectural significance).

Did you know: The Government can force you to take medications against your will.

And Bush plans to screen all public school students. [second dose]

Current Status & Disposition

Jan 2005: The Community/Activity Center was not approved for historical protection and is slated for demolition. (see That Damned Center below) Apparently, the older buildings on the original eight acres are historical sites, especially the main lodge and those structures on the front eight acres adjoining West Montgomery Ave.

There is a limited window of time.

Rockville, MD Planning Design Guidelines 2004 PDF

Maryland Historic Trust Building Inventory 2004

Woodlawn Hotel, a.k.a. Chestnut Lodge

Washington DC’s only remaining resort hotel, built just outside Rockville, Maryland, in 1886 as a summer boarding house and named for 125 chestnut trees on its twenty acres, Chestnut Lodge was operated as a “sanitarium for the care of nervous and mental diseases” by the Bullard family for nearly a century.

As the center of commerce and legal affairs for Montgomery County, Rockville was a fine locale for hotels. Beginning in the 1750s, travelers, courthouse clientele, salesmen, and visitors to the Court House town stayed at Lawrence Owen’s ordinary, Charles Hungerford’s tavern, Francis Kidwell’s Farmers Hotel, the Washington Hotel, the Union Hotel (rebuilt as the Corcoran), the Montgomery House, and others.

The arrival of the B&O railroad in 1873 changed the town. Rockville became a destination for city-dwellers wanting to spend a weekend, holiday, or summer in the country. In addition to the hotels around Court House Square, summer visitors took rooms in local boarding houses or made arrangements to stay in private homes.

In 1886, Charles G. Willson purchased five acres west of the town of Rockville, hired an architect, and began to build a large, four-story brick “summer boarding house.” Before the building was completed, Willson filed for bankruptcy. Among those looking at the building were the Trustees of the Rockville Academy. The unfinished hotel and adjoining three acres were bought for $6,000 by Mary J. Colley, proprietress of the Clarendon Hotel in Washington, D.C., and her partner Charles W. Bell.

When the Woodlawn Hotel opened for business in the spring of 1889, it was an immediate success. Summer guests, many of whom were prominent D.C. residents, enjoyed social gatherings, musical soirees, card games, dances, walks among the trees and cool country breezes. Ads for the Woodlawn boasted electric bells, gas lighting, artesian water, fresh country vegetables, breezy porches, and 40 guest rooms. Visitors usually came by train, traveling the mile from the railroad station to the hotel by carriage.

Rockville’s “boom” continued into the Gay Nineties, until a series of depressions deflated the economy. Many summer boarders, such as Edwin and Lucy Smith, decided to build year-round residences on lots in new subdivisions opening around Rockville. They liked living in a small town convenient to federal government jobs in Washington. However, by 1906, the Woodlawn’s owners, heavily in debt, had to sell. The hotel, stable, windmill, ice house, carriage house, laundry and servants quarters, and eight acres went to public auction.

The hotel was purchased by Dr. Ernest L. Bullard, a surgeon and professor of psychiatry and neurology from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Dr. Bullard renovated the hotel, by that time at the end of the trolley line. In 1910, he opened a sanitarium for the care of nervous and mental diseases, naming it for the 125 chestnut trees on the property. For many years, Dr. Bullard was the sole physician. For more than 75 years, three generations of Bullards operated Chestnut Lodge. The private hospital became known nationally for the quality of care and treatment, based upon the Bullards’ philosophy that mental illness is treatable through a combination of psychoanalysis and occupational therapy. Well-known therapists, such as Frieda Fromm-Reichmann and Otto Will, joined the staff. Through the years, the Bullards added acreage and buildings to their property, and made their home at Rose Hill.

By 1997, Rockville had changed and so had the Bullard family. CPC Health, a nonprofit corporation, purchased the portion of Chestnut Lodge facing West Montgomery Avenue, but declared bankruptcy three years later. From 2001 to 2003, Rockville’s only remaining resort hotel was owned by the Washington Waldorf School. In December 2003, the property was conveyed to Chestnut Lodge Properties, Inc.

Ownership history:

- Chestnut Lodge Properties, Inc. (Dec 2003-present)

- Washington waldorf school (2001-2003) WWS

- CPC Health (1997-2001, bankruptcy)

- 3 generations of Bullard family, Dr. Bullard (1906, 1910-1997)

- Woodlawn Hotel (Colley of DC’s Clarendon hotel, Charles Bell, 1889)

- Willson as a “summer boarding house.” (Willson, 1886)

As the center of commerce and legal affairs for Montgomery County, Rockville was a fine locale for hotels. Beginning in the 1750s, travelers, courthouse clientele, salesmen, and visitors to the Court House town stayed at Lawrence Owen’s ordinary, Charles Hungerford’s tavern, Francis Kidwell’s Farmers Hotel, the Washington Hotel, the Union Hotel (rebuilt as the Corcoran), the Montgomery House, and others.

The arrival of the B&O railroad in 1873 changed the town. Rockville became a destination for city-dwellers wanting to spend a weekend, holiday, or summer in the country. In addition to the hotels around Court House Square, summer visitors took rooms in local boarding houses or made arrangements to stay in private homes.

In 1886, Charles G. Willson purchased five acres west of the town of Rockville, hired an architect, and began to build a large, four-story brick “summer boarding house.” Before the building was completed, Willson filed for bankruptcy. Among those looking at the building were the Trustees of the Rockville Academy. The unfinished hotel and adjoining three acres were bought for $6,000 by Mary J. Colley, proprietress of the Clarendon Hotel in Washington, D.C., and her partner Charles W. Bell.

When the Woodlawn Hotel opened for business in the spring of 1889, it was an immediate success. Summer guests, many of whom were prominent D.C. residents, enjoyed social gatherings, musical soirees, card games, dances, walks among the trees and cool country breezes. Ads for the Woodlawn boasted electric bells, gas lighting, artesian water, fresh country vegetables, breezy porches, and 40 guest rooms. Visitors usually came by train, traveling the mile from the railroad station to the hotel by carriage.

Rockville’s “boom” continued into the Gay Nineties, until a series of depressions deflated the economy. Many summer boarders, such as Edwin and Lucy Smith, decided to build year-round residences on lots in new subdivisions opening around Rockville. They liked living in a small town convenient to federal government jobs in Washington. However, by 1906, the Woodlawn’s owners, heavily in debt, had to sell. The hotel, stable, windmill, ice house, carriage house, laundry and servants quarters, and eight acres went to public auction.

The hotel was purchased by Dr. Ernest L. Bullard, a surgeon and professor of psychiatry and neurology from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Dr. Bullard renovated the hotel, by that time at the end of the trolley line. In 1910, he opened a sanitarium for the care of nervous and mental diseases, naming it for the 125 chestnut trees on the property. For many years, Dr. Bullard was the sole physician. For more than 75 years, three generations of Bullards operated Chestnut Lodge. The private hospital became known nationally for the quality of care and treatment, based upon the Bullards’ philosophy that mental illness is treatable through a combination of psychoanalysis and occupational therapy. Well-known therapists, such as Frieda Fromm-Reichmann and Otto Will, joined the staff. Through the years, the Bullards added acreage and buildings to their property, and made their home at Rose Hill.

By 1997, Rockville had changed and so had the Bullard family. CPC Health, a nonprofit corporation, purchased the portion of Chestnut Lodge facing West Montgomery Avenue, but declared bankruptcy three years later. From 2001 to 2003, Rockville’s only remaining resort hotel was owned by the Washington Waldorf School. In December 2003, the property was conveyed to Chestnut Lodge Properties, Inc.

Historical Information

The opening of the Metropolitan Branch of the B&O Railroad in 1873 expanded Rockville’s role in Montgomery County. In addition to being the center of commerce and county government, rail service enabled Rockville to become a summer resort destination and a commuter suburb to Washington, D.C. Several hotels were constructed after the railroad opened and attracted urban residents who wished to escape to the country for the summer or a portion of it.

Charles G. Willson bought a parcel of land from the estate of Rebecca Veirs in 1886 and purchased another parcel from John P. Mulfinger and wife a year later. The acquisitions totaled five acres along West Montgomery Avenue. Willson began construction of a large, four-story brick “summer boarding house” there in 1886 but he went bankrupt before the building was completed. It was sold at auction and described as follows in a legal document dated April 18,1887:

The improvements consist of a large four story Brick Building with a front of forty feet by seventy feet in depth, four stories in height with basement for kitchen and dining room, now in the course of erection and nearly completed… The brick building has been artistically designed by a skilled architect for a Summer Boarding House and with its natural surroundings will make one of the most attractive suburban resorts in the vicinity of Washington…also the following personal property which is suitably adapted to the completion of said Brick Building; viz, Lot of doors, window frames, weather boarding, flooring, posts for porches, shingles, bricks, rough boards and other building material.[1]

[1] Liber JA #4, Folio 303, Exhibit No. 1. Montgomery County Land Records

The property was then sold to Mary Colley, proprietress of the Clarendon Hotel in Washington, D.C. and her partner, Charles Bell, in 1889. Mrs. Colley also purchased lots 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the adjacent Rebecca Veirs Addition at about the same time to create an 8-acre parcel. The following was printed in the Montgomery County Sentinel on April 19, 1889:

“Mrs. Mary J. Colley and Mr. Charles W. Bell of Washington city [sic], have purchased through Mr. C. P. Luckett the unfurnished brick hotel at the west end of this town, with eight acres of land adjoining, for $6,000. It will require $4,000 to finish the building and it is expected to be ready for occupancy by the 1st of June next. The purchasers intend to carry on the hotel business in the building and make it the most attractive house of the kind on the line of the Metropolitan Branch Railroad.[2]

[2] “Local and Personal-Town and Country.” Montgomery County Sentinel. XXXIV (April 19, 1889)

The Woodlawn Hotel opened for business in 1890. It catered to summer visitors, many of whom were prominent D.C. residents. Guests typically arrived by train and traveled the one mile west from the train station to the hotel by carriage. The Woodlawn had 40 guest rooms and contemporary amenities such as gas lighting, electric bells and artesian well water. Rockville’s resort boom continued through the 1890s and some summer boarders built year-round houses in the growing town. But the boom was over by 1906 and the owners of the Woodlawn were forced to sell the hotel at public auction.

The auction was advertised and the hotel was described as a “large and handsome brick building, three stories and basement, in a beautiful grounds containing eight acres of land.” The advertisement noted that the hotel contained about forty conveniently arranged rooms, running water, an on-site gas plant that furnished gas for lighting and gas fixtures throughout the structure. The hotel was described as having porches on all three floors (since removed), a three-acre lawn in front, and situated in a grove of natural forest trees, including chestnut, oak and pine. A two-story frame building used as a laundry with servants’ quarters above and a stable and carriage house were included. The property was advertised as suited for a hotel, sanitarium or school.

In 1908, Dr. Ernest L. Bullard (1859-1931) acquired the defunct Woodlawn Hotel and, over the next year and a half, renovated it for his private mental health sanitarium. Over the years, some of the decorative elements were removed but the basic massing, silhouette and major composition of roof, fenestration and integral trim were retained. Central heating, electricity and modern plumbing were added. Dr. Bullard named the facility Chestnut Lodge for the 125 chestnut trees that were on the property at the time before they were destroyed by blight and replaced by other species.

Dr. Bullard began caring for patients in 1910. His wife, Rose, ran the administration end of the business and their son, Dexter, joined his parents as the hospital’s assistant physician in 1925. Dexter married Anne W. Wilson in 1927 and the young couple was almost immediately put in charge of running the hospital as the elder Bullards departed on a trip. Anne eventually became the hospital’s business administrator.

The Bullard family quickly achieved a national reputation in the treatment of mental and nervous disorders. After Dr. Ernest Bullard died in 1931, Dr. Dexter Bullard changed the focus of the hospital to Freudian psychoanalysis. Dr. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann joined the staff in 1935. Dr. Fromm-Reichmann is recognized as one of the leaders in the field of mental health, particularly in the treatment of schizophrenia. Dr. Dexter Bullard had the Frieda Fromm-Reichmann Cottage built for her in 1936 to entice her to stay at Chestnut Lodge despite other job offers. She stayed there until her death in 1957. Other outstanding doctors worked at Chestnut Lodge from the 1930s through the 1990s.

Expansion for housing of the staff began in the 1920s and continued through the 1930s. The Bullard family’s first home on the premises is now called the Little Lodge and was built around 1929 shortly after Dexter and Anne Bullard married and moved to the Lodge property. In 1935, the Bullards purchased the 41-acre Rose Hill Farm that adjoined Chestnut Lodge on the south and extensively renovated and modernized the farmhouse to use as their home. The Bullards began laying down roads and playing fields among the barns and outbuildings of Chestnut Lodge and Rose Hill in the 1930s. Eventually many of the farm buildings were transformed into doctors’ offices and recreation facilities.

In 1945, the 115-acre farm, “The Maples” was purchased and converted for patient treatment and housing and renamed Hilltop House. Additional bursts of development activity occurred after World War II and in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the construction of office, research and recreational buildings located south of the original hotel building and its extant accessory structures. Four new brick patient buildings were added in 1987. Several houses on Thomas Street were also purchased for transitional patient housing.

The Maples farm was bisected by the construction of Interstate-270 and some of the property west of the highway was developed as a residential subdivision. Part of the southern portion of the property east of the highway was sold to the Montgomery County Board of Education as the site for Julius West Middle School.

In 1995, all of the remaining property owned by the Bullard family was put up for sale. It was eventually sold as two large parcels. The rear 40.69-acre portion fronting Great Falls Road was sold for single-family residential development and the front 20.43-acre campus was sold to Community Psychiatric Centers (CPC Health) to continue its use as a mental health facility. The Washington Waldorf School purchased the CPC portion in 2001.

The Bullard family lived in the “Little Lodge” from early 1900s until 1930.

Structures & Buildings:

Chestnut Lodge (4+ stories, brick)

Fromm-Reichmann’s cottage

Upper Cottage (nurses dormitory)

Guard House

Pump House

Sullivan House

Meyer House

White House

Greenhouse

Bus Shelter

Pool & Deck (south of gym)

Gym / Art Studio / Dance

Doctor’s Office Building

Maintenance Building

Community Center / Activity Building

Stanley House

Wood Shop

Barn

Milk Store

Ice House

Updates

23 Jan 2025

Some years ago, chestnut Lodge burned and was razed. Involvement of DEW in the “phyre” was considered but no persuasive evidence found. Its arson appears to have been by traditional means.

14 Aug 2007

I recently read the book and watch the video – Tuesdays with Morrie. The video was as good as the book. It shows the main lessons to be learned in the book. It is a good addition to the book as not everybody wants to read. Video allows the book to reach more learners. One event that I feel that is good to feature in the video but was not was what Morrie learn from working at Chestnut Lodge ( mental hospital ). He learned that people want someone to notice their existence and money cannot buy happiness.

Tuesdays with Morrie

Mich Albom

Page 109 – 111

Doubleday

ISBN: 0385496494

The Morrie I knew, the Morrie so many others knew, would not have been the man he was without the years he spent working at a mental hospital just outside Washington, D.C., a place with the deceptively peaceful name of Chestnut Lodge. It was one of Morrie’s first jobs after plowing through a master’s degree and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Having rejected medicine, law, and business, Morrie had decided the research world would be a place where he could contribute without exploiting others.

Morrie was given a grant to observe mental patients and record their treatments. While the idea seems common today, it was groundbreaking in the early fifties. Morrie saw patients who would scream all day. Patients who would cry all night. Patients soiling their underwear. Patients refusing to eat, having to be held down, medicated, fed intravenously.

One of the patients, a middle-aged woman, came out of her room every day and lay facedown on the tile floor, stayed there for hours, as doctors and nurses stepped around her. Morrie watched in horror. He took notes, which is what he was there to do. Every day, she did the same thing: came out in the morning, lay on the floor, stayed there until the evening, talking to no one, ignored by everyone. It saddened Morrie. He began to sit on the floor with her, even lay down alongside her, trying to draw her out of her misery. Eventually, he got her to sit up, and even to return to her room. What she mostly wanted, he learned, was the same thing many people want – someone to notice she was there.

Morrie worked at Chestnut Lodge for five years. Although it wasn’t encouraged, he befriended some of the patients, including a woman who joked with him about how lucky she was to be there “because my husband is rich so he can afford it. Can you imagine if I had to be in one of those cheap mental hospitals?”

Another woman – who would spit at everyone else took to Morrie and called him her friend. They talked each day, and the staff was at least encouraged that someone had gotten through to her. But one day she ran away, and Morrie was asked to help bring her back. They tracked her down in a nearby store, hiding in the back, and when Morrie went in, she burned an angry look at him.

“So you’re one of them, too,” she snarled.

“One of who?”

“My jailers.”

Morrie observed that most of the patients there had been rejected and ignored in their lives, made to feel that they didn’t exist. They also missed compassion – something the staff ran out of quickly. And many of these patients were well-off, from rich families, so their wealth did not buy them happiness or contentment. It was a lesson he never forgot.

SOURCE: http://whatidiscover.vox.com/library/post/chestnut-lodge.html

23 Feb 2008

Ted Koppel, on his final Nightline broadcast (2005), broadcast his 1995 interview with Morrie Schwartz. Morrie is a subject of the bestseller (and movie) “Tuesdays With Morrie” which contains details about Chestnut Lodge. There’s even a Broadway production and a website: tuesdayswithmorrie.com. Please note these great works only mention Chestnut Lodge in passing (there’s that unspoken undercurrent thing again), though the information they convey offers insight into conditions and treatment. An excerpt (from the TWM site):

ALS (aka “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”) is like a lit candle: it melts your nerves and leaves your body a pile of wax. Often. it begins with the legs and works its way up. You lose control of your thigh muscles, so that you cannot support yourself standing. You lose control of your trunk muscles, so that you cannot sit up straight. By the end, if you are still alive, you are breathing through a tube in a hole in your throat, while your soul, perfectly awake, is imprisoned inside a limp husk, perhaps able to blink, or cluck a tongue, like something from a science fiction movie, the man frozen inside his own flesh. This takes no more than five years from the day you contract the disease.

Quoted from immediately below: “Morrie was given a grant to observe mental patients and record their treatments. While the idea seems common today, it was groundbreaking in the early fifties. Morrie saw patients who would scream all day. Patients who would cry all night. Patients soiling their underwear. Patients refusing to eat, having to be held down, medicated, fed intravenously.”

21 Aug 2007

This email came in from Vicky at Chase Communities, the developer of the new Chestnut community: “Chestnut Lodge is NOT abandoned and it is dangerous to go onsite during the construction and building process. Demolition of the majority of the buildings has occurred and development has commenced on the property. A Security Company is assigned to Chestnut Lodge and a Neighborhood Watch is in place. It is incumbent upon you as a responsible internet website to advise your readers that we have, and will continue to, prosecute trespassers to the fullest extent of the law.” So, keep that in mind people: it’s not nice to trespass, it’s not right, and they will prosecute you if you’re caught. The Chestnut development is a multi-million dollar undertaking, so paying some lawyers to nab ne’er-do-wells is certainly within scope and capability.

Book on Frieda Fromm-Reichmann

Redeeming Frieda: How one psychotherapist fought the demons of schizophrenia. – ‘To Redeem One Person Is To Redeem the World’ – book review by Psychology Today, March-April, 2002 by Paul Chodoff

TO REDEEM ONE PERSON IS TO REDEEM THE WORLD (Free Press, 2001) Gail Hornstein, Ph.D.

You may have missed the news item about the demise of Chestnut Lodge, a psychiatric hospital near Washington, D.C. The bankrupt hospital was sold at auction last spring, a victim, in part, of managed care. The news disturbed me, for Chestnut Lodge was the domain of Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, whom I met more than 50 years ago in the course of my psychoanalytic training.

Frieda, one of the 20th century’s most prominent psychotherapists, was deeply committed to the American belief that a determined effort can solve any problem. She devoted her optimism–and her life–to treating the most intractable of all mental health problems: schizophrenia. Her efforts are the focus of Dr. Gail Hornstein’s book, To Redeem One Person Is to Redeem the World.

Born in 1889 to an Orthodox Jewish family in Germany, Frieda held onto her heritage throughout her life. Indeed, the mystical doctrine of Tikkun–to redeem one person is to redeem the world–was key to her approach to treating schizophrenics. Bright and energetic, Frieda completed medical school and became a psychiatrist. During World War I she worked with Kurt Goldstein, who did groundbreaking research on brain damage.

After the war, Frieda undertook training in psychoanalysis in Berlin, first somewhat negatively with Hanns Sachs, one of Freud’s disciples, then more positively with Georg Groddeck, one of Freud’s contemporaries. Groddeck’s conviction that psychotherapy could cure anything–even cancer–certainly influenced Frieda’s attitude toward schizophrenia.

As Frieda’s career prospered, she opened a sanitarium in Neuenheim, Germany, where she became Erich Fromm’s analyst–then his lover. Today her behavior would be considered a serious breach of ethics, but then it was merely the stuff of gossip. They married in 1927.

In 1935–after Hitler’s rise shattered her career–Frieda left Germany and eventually ended up at Chestnut Lodge. She remained at the lodge for 30 years and, with Harry Stack Sullivan, led a group of young analysts devoted to treating schizophrenics. Underlying Frieda’s approach was the assumption that schizophrenia’s symptoms are the patient’s desperate efforts to escape terrors induced by childhood psychological trauma. Frieda regarded schizophrenia not as a medical illness but as a way of living. She believed that psychotherapy could vastly improve the lives of some patients, provided that the therapist rejected all dogma and was willing to do anything to help.

How successful was the effort? Do Frieda’s methods have merit, or are they rightly condemned by the biological juggernaut that psychiatry is becoming? The book offers no clear answer. Hornstein, a psychology professor at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, attempts to be fair, but her heart is clearly with Frieda and psychotherapy. She acknowledges that many patients had prolonged hospitalizations with persistent and serious symptoms, but she also makes frequent, rather vague assertions that many patients did well.

Chief among the apparent successes is Joanne Greenberg, who later wrote about her illness and treatment in her autobiographical novel, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. The book made Frieda into something of a cult icon. Yet there is considerable controversy about the case: While some point to Greenberg as proof of psychotherapy’s healing powers, others argue that Greenberg never had schizophrenia. Among the failures is Herman Brunck, who did not recover and later committed suicide. Hornstein defends Frieda against the allegation that Frieda’s incompetence was responsible for his continued illness and subsequent death. She also defends Frieda’s use of the term “schizophrenogenic mother,” a phrase that suggests mothers cause the disorder.

Perhaps the most cogent piece of evidence offered on the efficacy of the lodge is found in a footnote summarizing results between 1910 and 1960. Of the patients discharged during this period, more than 70 percent were judged improved. This is not very informative, however, since Hornstein asserts that “the lodge counted almost any change as improvement.”

Readers will no doubt argue the merits of Frieda’s views on the nature of schizophrenia and the value of psychotherapy in its treatment. But I think they will agree that Hornstein’s book is a lively, well-written account of a charismatic leader in an important period of psychiatry’s history. A period that now appears to be fading fast.

Paul Chodoff, M.D., has been a practicing psychiatrist for more than 50 years. He met Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in 1950 during his training in psychoanalysis.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Sussex Publishers, Inc. // COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group

That damned UGLY Center

The recent ‘historic hoopla’ over Chestnut Lodge sadly focuses on what is honestly the ugliest, most-rundown, most unsightly, least useful, and shittiest building on the property, “The Center” (the community/activity building). The only reasonable explanation is, “there goes bumbling government again.”

Rose Hill Mansion, 215 Autumn Wind Way, March 2001

Although the Rose Hill mansion has been linked to the Bullard family of Chestnut Lodge for 2/3 century, the place goes back much farther in time. Eliza Wootton received 440 acres of land when she married Lewis Beall (brother of Montgomery County Clerk Upton Beall) in 1803. Their house was replaced with the current one by the 1840s. Eliza’s second husband, Rev. John Mines, Presbyterian minister for Cabin John and Bethesda parishes and principal of the Rockville Academy, referred to “Rose Hill” in a volume of poetry he wrote in 1837.

Several Rockville notables, including attorney Edward Peter, local master builder Edwin West, and county health officer Claibourne Mannar later owned the farm. In 1935, Anne and Dexter Bullard, Sr. purchased Rose Hill. They remodeled and modernized the house, and raised dairy cows to support some of the sanitarium’s operations. Rose Hill’s place in local history is its status as an early farmhouse and its long-time associations with individuals prominent in Rockville. Recent research by Peerless Rockville Docent Beth Rodgers uncovered a personal account of her family’s life at Rose Hill.

from Rockville MD Org

“Patricia Woodward also spoke as a citizen and former Head Nurse at Chestnut Lodge. She stated that the building was never called the Community Center, but the Activity Center. She related that Dr. Bullard’s and Dr. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann’s forte was psychotherapy and part of the treatment was establishing contact with other persons and accepting responsibility. She said that there were seven treatment units at the hospital, each with its own medical doctor, head nurse, nursing staff and activities personnel. The Activities Building was used as part of the treatment regimen, but not the treatment itself. Activities happened in every unit, which were in a home-like setting. As patients began to improve and desire more latitude and privileges, they were allowed to go to the Activity Building escorted, then unescorted, with requirements to notify staff on arrival and departure. As the sense of responsibility and accountability developed and was proven, the patient was allowed more freedom. In that sense, Ms. Woodward explained, the Activities Building was not a place for treatment, but was a reward for improvement and part of an overall encompassing regimen. She said that if saving the Activities Building resulted in the loss of the proposed museum in the Frieda Fromm-Reichmann house, the City and its citizens would be the primary loser.”

Cable History Show

Montgomery County Council

5 Mar 2003 // for immediate release

Contact: Patrick Lacefield 240-777-7939 or Jean Arthur 240-777-7934

COUNTY CABLE HISTORY PROGRAM FOCUSES ON CHESTNUT LODGE

This month’s edition of County Cable Montgomery’s “Paths to the Present: Montgomery County Stories” explores historic Chestnut Lodge in Rockville.

Chestnut Lodge had its beginnings in 1897 as a summer resort hotel. Originally named the Woodlawn Hotel, this four-story, Empire-style brick structure boasted all the modern amenities available at the end of the 19th century. But in less than 10 years, Rockville’s “resort boom” was over and the Woodlawn Hotel had to be sold. Ernest Bullard, a psychiatrist from Milwaukee, purchased the property in order to open a psychiatric sanitarium. He renamed it “Chestnut Lodge,” for the 125 chestnut trees that surrounded the main building at the time.

For nearly a century, three generations of Bullards owned and operated Chestnut Lodge. Throughout the years, it expanded and grew, gaining a place of international prominence in the psychiatric community. The Lodge was closed and grounds sold in 2001.

This show looks at the history of Chestnut Lodge and features reminiscences with James Bullard, who grew up on the property, as well as interviews with Dr. Ann-Louise Silver, a former employee at Chestnut Lodge, and with Eileen McGuckian, Executive Director of Peerless Rockville.

“Paths to the Present: Montgomery County Stories” is an on-going series highlighting this county’s local history and is jointly produced by the Montgomery County Council and the Montgomery County Historical Society. It can be seen on County Cable Montgomery (channel 6 on Montgomery County Cable) through April 5.

Hospital Data

http://www.hospital-data.com/hospitals/CHESTNUT-LODGE-HOSPITAL-ROCKVILLE.html

CHESTNUT LODGE HOSPITAL – ROCKVILLE, MD

500 WEST MONTGOMERY AVENUE, ROCKVILLE, MD 20850

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS

Services provided by CHESTNUT LODGE HOSPITAL:

Beds – Total (Total number of beds in a facility, including those in non-Participating or non-licensed areas): 110

Beds – Total certified (Number of beds in Medicare and/or Medicaid certified areas within a facility): 110

Physicians (The number of full-time equivalent physicians employed by a provider): 11

Change of ownership counter (The number of times a change of ownership (chow) has taken place for a particular provider): 2

Prior change of ownership (The date of a prior change of ownership): Aug 1996

Accreditation effective date (The effective date of the current period of accreditation by the joint commission on accreditation of health care organizations (jcaho) or the american osteopathic association (aoa)): Oct 1996

Accreditation expiration date (The expiration date of the current period of accreditation by the joint committee on accreditation of health care organizations (jcaho) or the american osteopathic association (aoa)): Oct 1999

Accreditation indicator (Indicates the organization that is responsible for the accreditation of the provider): JCAHO

Clia – Hosp lab id #1 (Number assigned to a hospital laboratory licensed in accordance with the clinical laboratory improvement act (clia)): 21D0212159

Current survey ever accredited (Indicates if this provider was an accredited hospital anytime during the current survey): Yes

Current survey ever non-Accred (Indicates if this provider was a non-Accredited hospital anytine during the current survey): No

Current survey ever swingbed (Indicates if this provider was a swingbed hospital anytime during the current survey): No

Dieticians (Number of full-time equivalent dieticians employed by a facility): 1

Medical school affiliation (The type of affiliation that a hospital may have with a medical school): NO AFFILIATION

Other personnel (The number of full-time equivalent other salaried personnel employed by a facility): 283.50

Participating code (y,n) (This code indicates whether a provider is participating in the Medicaid or Medicare program): Yes

Program participation (Indicates if the provider participates in Medicare, Medicaid, or both programs): MEDICARE AND MEDICAID

Registered nurses (The number of full-time equivalent registered professional nurses employed by a provider): 43.50

Resident program approved by ada (Indicates if the resident program at a hospital is approved by the american dental association): No

Resident program approved by ama (Indicates if the resident program at a hospital is approved by the american medical association): No

Resident program approved by aoa (Indicates if the resident program at a hospital is approved by the american osteopathic association): No

Resident program approved by other (Indicates if the resident program at a hospital is approved by other professional organizations): Yes

Srv: dietary (Indicates how dietary services are provided): PROVIDED BY STAFF AND UNDER ARRANGEMENT

Srv: home care unit (Indicates how home care services are provided by a hospital): PROVIDED UNDER ARRANGEMENT

Srv: laboratory (clinical) (Indicates how clinical laboratory services are provided in a hospital): PROVIDED UNDER ARRANGEMENT

Srv: pharmacy (Indicates how pharmacy services are provided): PROVIDED UNDER ARRANGEMENT

Srv: psychiatric (Indicates how psychiatric services are provided by a hospital): PROVIDED BY STAFF

Srv: radiology (diagnostic) (Indicates how diagnostic radiology services are provided by a hospital): PROVIDED UNDER ARRANGEMENT

Srv: social (Indicates how social services are provided): PROVIDED BY STAFF

Swing bed indicator (Indicates if a hospital provides swing bed services – Beds can be used for either hospital or long term care services): No

Type of facility (Indicates the category which represents the type of facility): PSYCHIATRIC

Medical social workers (Number of full-time equivalent medical social workers employed by a hospital or hospice): 49

Compliance: plan of correction (Indicates if a provider is in compliance with program requirements based on an acceptable plan for correction of deficiencies): COMPLIANCE BASED ON ACCEPTABLE POC

Compliance: status (Indicates if a provider or supplier is in compliance with program requirements): IN COMPLIANCE

Eligibility code (Indicates if a facility is eligible to participate in the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs): ELIGIBLE TO PARTICIPATE

Participation date (The date a facility is first approved to provide Medicare and/or Medicaid services): Jan 1993

CPC Info

CPC HEALTH: Mental Health Provider Files Chapter 11 in Greenbelt, Maryland

The Washington Post reports that mental health provider CPC Health Corp. filed for bankruptcy reorganization under Chapter 11 in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Greenbelt, Maryland. According to court documents, the Rockville firm will continue to operate. President Steven Goldstein said that even though layoffs are not planned yet, it might change after a careful review. “Buried in this great range of programs are probably certain services that are either under-reimbursed or poorly performing on the financial side,” Goldstein added. Health Care Business Credit Corp., which has lent $6.5 million to CPC, is considered its largest creditor.

CPC Health posted assets of $15 million and debts amounting to $11 million upon filing. Many of those assets consist of land and buildings that aren’t easy to convert to cash. CPC consists of 450 workers and 34 psychiatrists and psychologists. CPC delivers a wide array of mental health services to 4,000 patients a year at Chestnut Lodge Hospital, residential and outpatient facilities, the Lodge School, three group homes and several programs within county public chools.

CPC bought CNL for $4million.

Original Website

These pictures are from the last original chestnutlodge.com website, circa 2001, after it was bought by CPC but before it closed. More coming soon. Meanwhile, domain name squatters hold chestnutlodge.com.

See also

There is some speculation that the arsonic razing of Chestnut Lodge may have involved Directed Energy Weapons, and while the evidence is weak the implication is interesting.

1:20 in “We couldn’t knock it down; we had to do something with it.”