CASE Hell House AKA St Marys College Roman Catholic Redemptorist Order in Ilchester Maryland

St. Mary’s College, later infamously known as “Hell House,” was established in 1868 by the Redemptorist Order in Ilchester, Maryland. The institution served as a seminary for young men aspiring to the priesthood, situated on a picturesque hilltop overlooking the Patapsco River. The campus featured a grand five-story brick building with a cupola, a chapel designed in a cruciform shape, and meticulously landscaped grounds. (Abandoned Country)

Despite its initial prominence, the college faced declining enrollment and ultimately closed its doors in 1972. Following its abandonment, the vacant structures became a magnet for vandals and thrill-seekers. The once-sacred site garnered a reputation for being haunted, with numerous legends of paranormal activity and alleged satanic rituals, earning it the moniker “Hell House.” (Ancient Origins)

In 1982, developer Michael Nibali purchased a portion of the property with plans to convert the building into apartments. However, after approval failed, the building was abandoned and subjected to vandalism. In 1987, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources acquired a significant portion of the site, annexing it to Patapsco Valley State Park. Despite these efforts, the main building was destroyed by arson on Halloween night in 1997, and the remaining structures were completely demolished in 2006. (Wikipedia)

Today, the site of St. Mary’s College remains a point of intrigue for urban explorers and those fascinated by its storied past. While the main structures no longer stand, remnants like the “Hell House Altar” can still be found, serving as a haunting reminder of the location’s complex history. (Only In Your State)

For a visual exploration of the site’s history and its eerie transformation, you might find this video insightful:

The Chilling Legend of Maryland’s Haunted Hell House College

In St. Mary’s College, Ilchester, Maryland (originally, “Mount Saint Clemens”) is the 100+ year old real “Hell House” near Ellicott city for the Redemptorist order of Roman Catholic church and not the oft confused Patapsco Female Institute (which is up on the hill in Ellicott city).

SpookyDan, Urban Atrophy: “[The property caretaker] was even charged with assault, battery and assault with the intent to murder in 1996 when he shot and critically wounded a trespasser. I don’t know what came of the charges but Hudson remained caretaker and continued living on the property.”

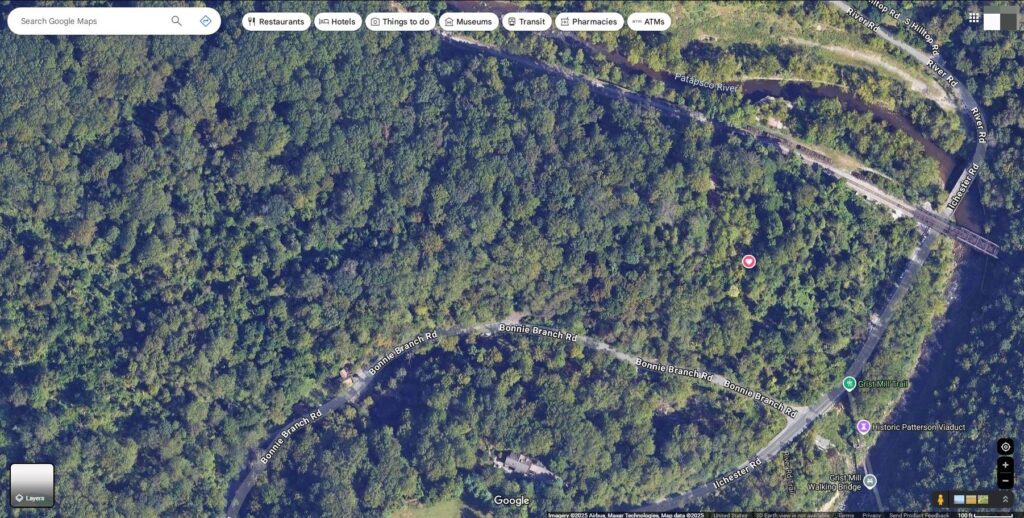

GOOGLE MAP

https://www.google.com/maps/@39.250538,-76.7682918,421m

See also

Simkins Paper Plant was immediately down the adjacent eastern slope. Its history of hauntings was probably at least somewhat related.

A History of St. Mary’s College in Ilchester, Maryland by Michael Duck, View 19 Oct 2000

Many area residents have seen the tall building rising out of the forest, overlooking the Patapsco River near Ilchester Road. Others have seen or heard of the mysterious old staircase leading up from the road and back into the woods.

Few people know the real story behind these structures, though. The building is what remains of St. Mary’s College, a seminary for young men joining a Roman Catholic religious order known as the Redemptorists. The college operated at that site for over a century.

Mary Mannix, former Library Director of the Howard County Historical Society, said that the college is one of the most popular research topics at the Historical Society. Mannix commented that, among Ellicott City topics other than the Patapsco Female Institute, “it’s probably the biggest single topic that people come looking for.”

The site has played an important role in the history of Ilchester ever since the town was established. Even before St. Mary’s College existed, the property’s owners figured significantly in the histories of Ellicott City and Ilchester.

Big Plans for Ilchester

In the early 1770s, Joseph, Andrew, and John Ellicott traveled from their homes in Bucks County, Pennsylvania to build a flour mill on the banks of the Patapsco River. The site they selected, of course, came to be known as “Ellicott’s Mills,” later renamed Ellicott City. The Ellicotts also acquired two miles of land up and down the river from where their mill was located, including present day Ilchester.

George Ellicott, Jr.- a grandson of Andrew Ellicott- had big plans for Ilchester. When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was built in 1830, the train passed near his homestead in Ilchester. Ellicott hoped that the town would become a regular stop for the large Western trains.

“He thought this would be a good stop on the railroad for the tourists,” explained Joetta Cramm, author of A Pictorial History of Howard County. “That’s why he built the ‘stone house’ here: he was going to operate it as a business.”

Ellicott established a tavern in his “stone house,” located a few hundred feet from the railroad, and built stairs leading down to the tracks. Though Ilchester seems awfully close to Baltimore to be considered a “countryside resort” by modern standards (just twelve miles away from the train), it was a long enough journey in the middle of the nineteenth century.

However, to Ellicott’s chagrin, his tavern didn’t become the successful business venture he had envisioned. The B&O Railroad selected Ellicott’s Mills as the major stop after Relay, rather than Ilchester. According to Ilchester Memories, a history of St. Mary’s College written by Rev. Paul T. Strott in 1957, stopping at Ilchester was “anything but convenient” for the large trains. Until the Ilchester tunnel was built in 1903, the trains had to go around a large hill and follow a sharply curving track. Trains that stopped at Ilchester would lose the momentum they needed to make it around that sharp bend.

According to Cramm, the trains would only stop if a passenger made a specific request to stop get off at Ilchester. Few passengers made that request.

Ellicott eventually decided to sell the property and his failing tavern. This proved difficult, though, due to Ilchester’s small size and its inconvenient location for starting a business.

Most Holy Redeemer

The group that eventually bought the property, however, wasn’t interested in starting a lucrative business. As Rev. Scott put it in Ilchester Memories, “The qualities that made it unfit for trade made it fit for the purposes [they] had in mind- retirement, study, and prayer.”

The Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, commonly known as the Redemptorists, was established by St. Alphonsus de Liguori in 1732. The first Redemptorists came to the United States in 1832. By the 1860s, the Redemptorists were looking to establish a Studentate within a reasonable distance of their provincial residence at St. Alphonsus Church in Baltimore.

They decided that Ellicott’s 110-acre property would suit their needs quite well. As Rev. Strott put it in Ilchester Memories, “it was looked upon as ideal for recollection and research.” Just as important, it was also close to a railroad, so supplies and students could be transported easily.

According to Ilchester Memories, George Ellicott, Jr. and Father Joseph Hempraecht (the Provincial) signed the Contract of Sale on June 12, 1866. The Redemptorists paid $15,000 for the 110-acre site, including Ellicott’s stone house and several farm houses. Rev. Joseph Firle celebrated the first mass on August 28, 1866 in a small room on the third floor of the stone house.

After selling the property, George Ellicott, Jr. moved to Ellicott’s Mills. In 1867, he became the first mayor of the newly-renamed “Ellicott City.”

The Redemptorists quickly set about building the new college. Members of the order designed the four-story “upper house,” which was erected in 1867. Classes began in September of 1868.

According to Rev. Strott’s account, the first community at the school consisted of 29 people, including three fathers- who made up the entire faculty- and nineteen students.

The college grew quickly. In 1872, the Redemptorists built on to the “lower house” (Ellicott’s original stone house), adding a wooden extension containing a chapel. Ten years later, they built a new chapel adjoining the “upper house.” Within a few decades, they also added a fifth floor to the upper house.

Cramm estimated that the upper house was probably built to accommodate 100-150 individuals.

The college was initially known as Mount Saint Clemens. In 1879, however, priests installed the “authentic picture” of Our Lady of Perpetual Help in the chapel, as Pope Pious IX had charged the Redemptorists to encourage devotion to St. Mary under the title of “Perpetual Help.” When the new chapel in the upper house was dedicated in 1882, the school was renamed St. Mary’s College.

So Many Boys

Ardellia Cugle Smith, who still lives near the old seminary, can remember the college at its height. “There were so many boys coming in at that time,” she recalled. “They used to be up on the hill…You could see them walking out through the field [to their] grotto up on the hill dedicated to Our Blessed Virgin Mary.”

Smith’s family has been involved with the Redemptorists from the time that the order bought the property from George Ellicott. Smith’s grandparents started working at the college shortly after it opened, with her grandmother doing laundry and her grandfather tending the furnace.

Many other local Catholic families also developed relationships with the Redemptorists at the college. Although the Catholics in Ilchester and nearby towns of Gray’s Mills and Thistle were considered parishioners of St. Paul’s Church in Ellicott City, many were too poor to travel to Ellicott City each week to attend mass. With the permission of the Archbishop, the Redemptorists ministered to the local residents and allowed them to participate in masses at the college chapel.

As the local Catholic community grew, James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, decided that a parish should be established in Ilchester. On February 12, 1893, the chapel in the lower house was reopened as a parish church dedicated to Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

The parish of Our Lady of Perpetual Help still exists, though in the late 1950s it moved to a more modern facility about a mile south on Ilchester Road. The Redemptorists continued to serve the parish until 1996, when the order turned it over to the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

The Redemptorists continued to operate St. Mary’s College through the 1960s, but steadily decreasing numbers of students eventually forced its closing in 1972.

“There were just so few boys coming in,” Smith explained. Like many Catholic religious orders, the number of young men entering the Redemptorist order has declined substantially. Smith said that the last class to graduate from St. Mary’s consisted of only about ten students.

“I went to the last graduation down there [when] one of the boys invited me,” she recalled. “It was really sad.”

The Redemptorists sold part of the property to the State of Maryland in 1987, contributing to the Patapsco Valley State Park. The rest of the land was sold to private interests.

Today, little remains of the college’s buildings. The lower house- including Ellicott’s stone house- was destroyed by a fire on June 14, 1968. According to Cramm, what remained after the fire was torn down, and an unidentifiable rubble pile is all that’s left of the structure.

More recently, the upper house was gutted by fire on November 1, 1997.

The history of the college has played a large role in shaping the local area, from its connection with Ellicott City’s first mayor to its role in the development of Ilchester.

“I just always enjoyed it because of its relationship with George Ellicott,” commented Cramm. “[It’s] fascinating.”

At the Historical Society, Mary Mannix said that her interest stems from the importance of the college itself.

“It was a major institution here in Howard County,” she said. “Not only was it important to the county and to Ellicott City itself, but people came from all over to be educated there. It was one of those buildings, like Patapsco Female [Institute] which, besides being of local interest, had a national reputation.”

No Trespassing

Nevertheless, amateur historians interested in doing their own research are strongly discouraged from visiting the property itself. What remains of the college’s upper and lower houses are located on private property, behind clearly visible “no trespassing” signs.

Cramm has always been careful to make this point clear in her course on local history which she teaches for Howard Community College. “I always told the story about it, but said, ‘You have no business going there.'”

The best way to get a view of the remains of the upper house is to hike to an overlook located within the Patapsco Valley State Park on the Baltimore County side of the river. A parking area on Hilltop Road marks the trailhead.

Individuals wishing to learn more about St. Mary’s College and its history are encouraged to visit the Howard County Historical Society Library. The library, which is located near the Ellicott City Circuit Court building, is open to the public from noon to 8 p.m. on Tuesdays and from noon to 5 p.m. on Saturdays.

Many say the place is haunted. Others used talk of satanic altars or drug labs hidden within the cavernous old building. And… people sacrificing goats?

Well, not really. These are just rumors surrounding the old St. Mary’s College in Ilchester, stories passed around among teenagers from all over the region. The students have a different name for the old seminary too: “Hell House.”

These rumors, with their focus on the occult and supernatural, have little basis in reality. The real story, however, is almost as unusual: There’s the owner, who allegedly splits his time between his home in India and his apartment complex in Savage. There’s the property’s caretaker, who apparently has lived for years in the shadow of the old buildings with his rottweilers and a shotgun, chasing off troublemakers. And then there are the vandals and trespassers- mostly teenagers who come to test their bravery or their foolhardiness, to make trouble, drink alcohol, and find out if all those rumors are really true.

“Kids party up there,” said Craig Phillips, who lives close by the old seminary. He said he often sees young people en route to the famous hangout; some even ask him for directions to Hell House.

“Whenever I see kids anywhere around here,” Phillips explained, “I always warn them. I say, ‘Just stay away.'”

Phillips isn’t warning them about spirits haunting the old school, however. He’s referring to a much more practical concern: Allen Rufus Hudson, the property’s caretaker. Hudson- sometimes called “The Hermit” or “The Hilbilly” by the teens- is a prominent figure in most of the stories about Hell House. Hudson has acquired a reputation for chasing trespassers off the property with his rottweilers and his shotgun (which according to one account, is filled with rock salt).

Nonetheless, “I can empathize with him,” commented Phillips. “Kids go up all the time and harass the hell out of him, from what I understand.”

Parties, Vandalism

Even properties near the old seminary sometimes have problems with vandals. Ardellia Cugle Smith, Phillips’s neighbor, routinely suffers vandalism on her property. “They have parties down at the bridge,” she said, “and we’ve had our windows blown out and shot out, [our] mailbox blown up…”

Smith said that the police told her to report such problems, but it just happens too frequently for her to call after each incident. “I’d be phoning them all the time,” she said.

There’s also a possibility that vandals were involved with the fire that burned down the college’s main building in the early morning of November 1, 1997- the day after Halloween.

State fire officials labeled the blaze as “suspicious,” but the ensuing investigation was inconclusive. At the time, Hudson reported that he had heard a “bang” at midnight, but found nothing when he investigated the sound. At 5 a.m., he heard another “bang,” and immediately saw the building in flames.

Officials encountered one juvenile on the scene, who refused to give names but said that there had been other juveniles who had entered the building.

Phillips, however, is pretty sure that teens were responsible for the fire. “On Halloween, it would make sense that that would be it.”

Howard County Police Spokesperson Sherry Llewellyn confirmed that the police are aware of the trespassing that occurs on the property. “The mystery of it seems to appeal to young people,” she explained. “We do have some concerns that there is some drinking going on there.”

However, she stressed that the trespassers are mostly engaging in “general mischief” rather than committing serious offenses.

“‘Mischief’ is really the key word here,” she said. “We’re not concerned that there are any serious crimes being committed. But it is a place that appeals to local kids, and we just monitor it to make sure that no one is breaking any laws.”

Air of Mystery

The property has long played a key role in the history of Ilchester and of Howard County. George Ellicott, Jr.- who went on to become the first mayor of Ellicott City- tried to develop a tavern on the site in the mid 1800s, but the venture proved a failure when the big trains on the B&O Railroad rarely stopped at Ilchester. The Redemptorists, a Roman Catholic religious order, then bought the property from him in 1866 and built a seminary. They added on to Ellicott’s tavern (the “lower house”) and also built the much larger “upper house” to accommodate the students. The Redemptorists operated the seminary there from 1868 until 1972, when it closed due to a lack of students. (The school was known as Mount Saint Clemens, until being renamed St. Mary’s College in 1882).

More recently, though, the property has fallen into disrepair. Part of the land was sold to the State of Maryland in 1987, becoming part of the Patapsco Valley State Park. The rest- which included the sites of the two buildings- was sold to private interests.

The Roman Catholic parish of Our Lady of Perpetual Help also grew out of Redemptorist ministries at the college. In the late 1950s, the parish moved from its facilities in the college’s “lower house” to its current location, about one mile south on Ilchester Road. In 1996, the Redemptorists left the parish as well, taking their histories with them.

Since then, Our Lady of Perpetual Help Parish has been administered by the Archdiocese of Baltimore. And the pastor, Rev. Richard Smith said that he knows nothing about the old property, its history, or its present owners.

“It’s existed,” he stated, “[and] that’s all I know.”

In fact, few people know anything about the present owners- including public officials. Since the property is privately owned, little information is available.

State tax assessment records indicate that the current owner is “BCS Limited Partnership,” supposedly located on the property itself. The only mailing address is a Savage, MD post office box, “c/o S&S Partnership.”

However, several sources named a “Dr. Singh”- in one account, Sateesh Kumar Singh- as the primary owner of the property. Singh was described as the owner either of BCS or of the “Kamakoti and Tirupati Foundation.” Singh was also said to own the River Island apartment complex in Savage.

A secretary at River Island reported that the apartment complex is owned by “Kamakoti Properties,” and confirmed that a “Dr. Singh” is involved in that company, though she could not confirm Singh’s first name. She also indicated that Singh lives both in Savage and in India.

Singh did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

Phone calls to “Tirupati Investors,” also located within the River Island apartment complex, received no response, either.

‘He Stays to Himself’

Allen Rufus Hudson, the property’s caretaker, is equally enigmatic. According to two local residents, Hudson often refers to the property as “his,” even though his claims of ownership are not supported. Hudson’s relationship with BCS or with Singh has never been documented publicly.

Some neighbors have never had a problem with Hudson. “I don’t know too much about him, because he stays to himself up there,” said Smith, whose property borders the old seminary’s grounds. “We just wave when he goes past.”

“I’ve really only seen him two or three times,” commented Susan Mullendore. “One of those was pleasant enough, one of those we didn’t speak at all, and the third one was… intense.” In that third encounter, Mullendore reported, Hudson was “very angry” about a pile of dirt and rock on the Mullendores’ property, which happened to be located across from Hudson’s driveway.

Overall, though, there has been little interaction. As Mullendore put it, “I don’t seek him out, and I don’t necessarily avoid him, but very little interaction has actually occurred.”

On the other hand, Phillips indicated that he had been warned to stay very far away from Hudson. “When I talked to the police -who know him well- I said [that I wished] I could be his ally,” explained Phillips, who lives near Hudson’s driveway. “I could help out, keep kids away and things. I mentioned that I kind of felt sorry for the guy.”

‘Stay Clear’

However, police discouraged him from contacting Hudson. “It was explained to me that he’s somebody absolutely, positively to stay very clear of,” recalled Phillips. “[They said,] don’t even begin to try to interact [with him] in any way, shape, or form. So, I’ve taken their advice.”

Hudson has been brought into court at least ten times since 1989, usually facing charges of assault and battery. Prosecutors dropped charges in most of the cases, but Hudson has also been convicted several times.

Hudson himself could not be reached for comment. It is unclear if Hudson is still living on the property or not.

‘Satanic Situation’

Mary Mannix, Former Library Director of the Howard County Historical Society, said that, before the fire, “We’d get students of various ages, from middle school up to college age, some of whom might have been hanging out or partying down there.” She said that some of these researchers had heard there was some sort of “Satanic situation” on the property.

Mannix believes that much of the interest surrounding St. Mary’s has been prompted by the old abandoned buildings themselves, combined with the mysterious nature of the owners. “It’s privately owned, [and] no one really knows what’s going on there,” she said. “Essentially, the building was going to waste for years… Also, the fact that it had this mysterious caretaker and it had large dogs barking- that that got people very interested. Because, [people think] obviously, if they don’t want you going near it, then there must be something going on there.”

Hurley noted that visiting the site, even with the caretaker’s permission, was a pretty spooky experience. At that time, Hurley said, Hudson was keeping his dogs inside the upper house. “We could hear the dogs barking in that cavernous, empty building,” he recalled. “It was really quite a sound.”

Many of the ghost stories that involve the property are notable for their inaccuracy. An account on www.ghostpage.com, a Web site operated by the Ghost Hunters of Baltimore, Intl., identifies “Hell House (Old St. Mary’s College” as an “old all girls school that has been abandoned.” The account continues, “People from the area that have been able to go there have seen and heard many spirits while visiting.”

(Mannix indicated that, for many years, both the Patapsco Female Institute ruins and the old St. Mary’s College ruins were known as “Hell House,” which may have contributed to this confusion.)

A more elaborate version of the story says that one student at the supposed “all girl” school wrote in her diary about how awful conditions at the school were and how much she wanted to leave. Eventually, according to the story, everyone at the school died of pneumonia. When another group tried to reopen the school, they encountered the ghosts of the girls from before, and began experimenting with “black magic” to keep the spirits at bay.

Local historian Joetta Cramm, author of A Pictorial History of Howard County, has also heard some stories pertaining to what she calls “this supernatural crap.” She has heard stories that “for years people have gone out there around Halloween, and waited for the supernatural spirits or whatever.”

Cramm is somewhat upset by these rumors, though. “It really disturbed me,” she said. “I mean, that was a sacred place.”

Nevertheless, the stories persist. And they probably will continue for as long as the buildings remain standing and rumors about the caretaker still circulate.

As Mannix pointed out, the mystery and danger hold a strong appeal to thrill-seekers.

“I know we’ve had a number of researchers who really were interested because of the fact they were chased off,” she commented. “Otherwise, they probably would have walked around, said, ‘Hey, that’s cool,’ and gone about their business. As opposed to going, ‘Well! We’re going to find out what’s going on there! Are they sacrificing goats?'”